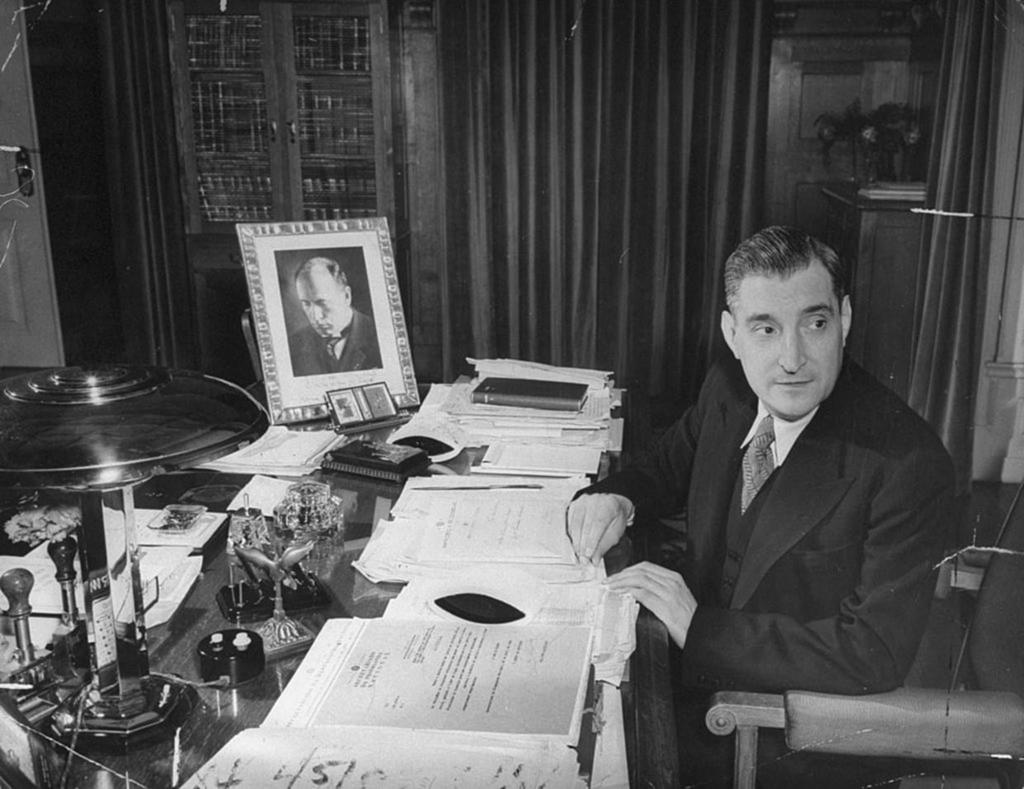

António de Oliveira Salazar and the Estado Novo : Shadows and Legacies of a Dictatorship

When I think back to my parents’ stories, leaving Portugal for France at the end of the 1960s, I see in them the reflection of an entire country that took to the road. Their departure wasn’t just a “change of scenery” : it was a flight, a gamble, a hope. And behind that decision lay the weight of Salazar’s long dictatorship, a regime that shaped Portugal for nearly forty years. (And to think that Portugal has only been “free” for about 50 years… yes, it really wasn’t that long ago !)

A regime takes hold

In 1932, Salazar became President of the Council of Ministers, and the following year, the 1933 Constitution officially established the Estado Novo regime. Portugal shifted from an unstable Republic to an authoritarian, national-corporatist state, inspired by Catholic and conservative ideology. The regime stood on several pillars : budgetary stability, tight political control, the suppression of trade union freedoms, and strict censorship enforced by the political police, the infamous PIDE. (And if you mention the PIDE, Salazar’s secret police, to my grandmother’s generation, believe me, they’ll have a lot to say… and all of it tinged with fear !)

Policies and daily life under the Estado Novo

Salazar liked to present his regime as the cure to the “anarchy” of the old Portuguese Republic : he controlled, reformed, and framed every aspect of life. Work, the economy, the family, the Church… everything was part of the same grand plan. There were tax reforms, efforts to balance the national budget (hence his nickname, the “magician of finance”), but also the establishment of a tightly controlled, state-run trade union system.

For many Portuguese people, that meant little political voice, few opportunities, and a very narrow horizon. In rural villages and working-class neighborhoods, the hope of “leaving” became the only way out.

Emigration as an escape valve

This is where my family’s story connects with that of the country : between the 1940s and 1970s, hundreds of thousands of Portuguese emigrated to France, Brazil, and Africa. They left for many reasons : in search of a better future, to avoid the colonial wars that dragged on until 1974, or simply because economic and political prospects at home were scarce.

My parents, like so many others, moved to France not only to work but to breathe a little more freely. This mass exodus left families divided, roots spread across two lands, and a collective memory made of nostalgia and longing.

April 25, 1974 and the legacy

The Estado Novo regime came to an end with the Carnation Revolution, that famous and beloved April 25, 1974, an almost peaceful uprising led by young army officers weary of the colonial war and citizens yearning for democracy. The dictatorship had lasted for more than forty years… a long, defining chapter of Portuguese history !

But its legacy didn’t vanish overnight. Portugal entered a democratic transition, but also faced new economic, social, and historical challenges. Even today, opinions about that period remain mixed.

Why it still matters today ?

Let’s be honest, 1974 wasn’t that long ago ! Just over 50 years, barely two generations. Some of our parents and grandparents lived both before and after : the fear of talking politics, radios that “bent the truth”, and neighbors suspected of being “with the PIDE”. Of course, that kind of thing leaves a mark.

Modern Portugal still bears that imprint : a certain distrust of government, a tendency to avoid “making waves”, and at the same time, a deep pride in having won freedom without bloodshed and with carnations ! It’s a country that moves forward slowly, carefully, but with heart. And if the Portuguese sometimes seem a little reserved or nostalgic, perhaps it’s because they’ve learned to be wary of noise, power, and too-good-to-be-true promises.

But you also can’t understand contemporary Portugal without recognizing that legacy : the big economic families, the urban layout of certain cities, the social fabric, all were shaped during Salazar’s rule. And for those of us whose parents left Portugal, it means carrying a family memory intertwined with “what we left behind” and “what we found”. The regime wasn’t as brutal as some neighboring fascist states, but freedom was still sorely missing.

Salazar and the Estado Novo aren’t just names in history books. They linger in every corner of the country : in the stones of old buildings, in family memories, in migration stories, and in the ongoing debates about democracy and freedom.

My own family story, my Franco-Portuguese roots, reminds me that, for some, leaving was a leap toward the light. And for Portugal, that regime was both a source of stability and stagnation.

Understanding that is also understanding the Portugal of today.

Share this article

Suggested articles

The Portuguese Colonial Empire, greatness and the end of an era

It is astonishing to think that a small country on the edge of Europe once ruled the seas and shaped global history. In the fifteenth century, Portugal, with barely over a million people, became the beating heart of the Age of Discovery. It was the age of sailors, dreamers and merchants who turned the unknown into possibility.

Amália Rodrigues, the diva who made fado shine across the world

Some artists do not just sing; they embody emotion, history and identity. Amália Rodrigues was one of those rare souls. Born in 1920 in Lisbon’s Mouraria district, she grew up among street vendors, laughter and hardship. There, she discovered fado, the music of love, loss and longing.

The Lisbon Earthquake of 1755 : an event that shook Europe

On November 1st, 1755 (All Saints’ Day), the city of Lisbon woke up to the sound of church bells, the faithful filled the pews… and suddenly, the ground began to shake. Around 9:40 a.m., an earthquake with an estimated magnitude between 8.5 and 9.0 struck the city, followed by a devastating tsunami and massive fires that tore through its neighborhoods… You’ve probably heard of it, right ?

April 25th : a revolution like no other (and with flowers, please)

It’s not every day that a dictatorship collapses… in a festive atmosphere filled with red bouquets ! And yet, Portugal pulled off that miracle. On April 25th, 1974, while Europe was quietly waking up, Lisbon was vibrating to the sound of a song Grândola, Vila Morena and the scent of a symbol that would become immortal : the red carnation.

The Age of Discovery : how the Portuguese changed the map of the world

Picture this : it’s the late 14th century. A small country on the edge of the Atlantic, sails in the wind, a few daring sailors, and one big dream to discover what lies beyond the horizon ! That’s how the incredible adventure of the Age of Discovery begins, with Portugal taking center stage. And no, it wasn’t just about sketching maps it was a full-on world revolution… and, let’s be honest, a massive “let’s go and see what happens” gamble (spoiler : it paid off).